by Meera Satpathy

Shyama is a 13-year old rag picker who lives in Sector 56 Slums an urban slum of the Millennium city of Gurugram. Even as she segregates the garbage in a landfill, she carefully puts any edible leftovers in a separate polybag to take home for her pregnant mother and infant brother. Not surprisingly, she is underweight, her mother is severely anemic, and her infant brother is showing signs of early stunting.

When Sukarya’s community outreach workers reached her house to hand over the COVID-19 hygiene kit and a basic dry ration packet as part of their COVID-19 community initiatives, they found Shyama sorting out her day’s collectibles from the landfill and trying to put some food on the table. It did not take long for the Sukarya volunteer to grasp the situation.

After two hours of counselling they could convince her mother to let her enroll in the Education on Wheels (EOW) programme run by them that provided children like Shyama an opportunity to avail of education through informal means while continuing to support their families. Currently they are in discussion with her mother to utilise her skills in a small cottage enterprise entailing drying and grinding of spices and bottling of pickles which several of the self help groups are preparing under Sukarya’s guidance.

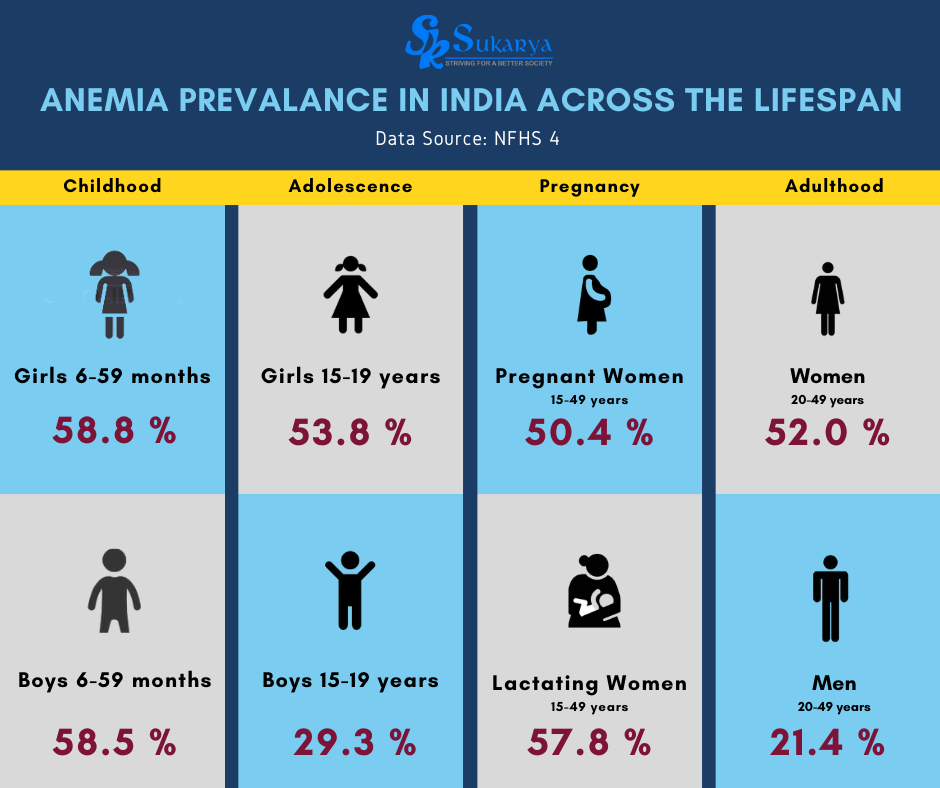

India has been a free country for over seven decades but is yet to gain freedom from anemia and malnutrition. Despite government programmes, PPP efforts, a strong NGO presence at the grassroots and countless community initiatives, the percentage of children, young adults and women who are anemic is still hovering at alarmingly high levels. While it is common knowledge that pregnant women, newborn infants, lactating mothers and adolescent girls suffer a huge nutritional disadvantage due to ignorance and a deep-rooted societal bias, an interesting revelation that emerges from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 4) data and which also correlates with Shyama’s domestic situation is that male infants too are just as anemic and malnourished as their female infant counterparts. Part of this is due to the mother being malnourished and anemic which affects the newborn and the rest of course due to poverty and lack of access.

Perhaps as these infants grow in an impoverished household, chances are that the male child will be given a more wholesome meal and the male adult too would get priority over the female, even if she is the primary breadwinner. The gender inequality plays out time and again and any amount of work done by NGOs like ours still leaves many areas that need to be addressed and messages that must be reinforced. Our experience has shown that there is a lot of native wisdom which exists in local communities and tribal population. In fact, each state has its own unique food which is abundantly available and also rich in nutrients. These need to be promoted. Our own food kits contain simple things like jaggery, ragi, jowar and bajra which are the staple food in so many communities, even among those who live below the poverty line. Advice like cooking in iron vessels to avoid depletion of iron and many other simple tips can be shared and propagated.

On this World Nutrition Day which falls on 28 May let us pledge to give our children – both boys and girls equal right to food and nutrition. That is our only hope to create a solid foundation on which they can build healthy and productive lives.